Evidence of Them: Digitization, Preservation, and Labor

This is a lightly edited version of the presentation I gave as part of as a part of Session 507: Digitization IS/NOT Preservation at the 2018 Society of American Archivists Annual Meeting. The session was overall pure fire, with thoughtful, funny, provocative, and challenging presentations by Julia Kim, Frances Harrell, Tre Berney, Andrew Robb, Snowden Becker, Fletcher Durant, Siobhan Hagan, and Sarah Werner. My heart goes out to all of them. All of the images used in the presentation were adapted from The Art of Google Books.

Good afternoon. I’m here to tell you that digitization is preservation of our prevailing societal context surrounding those projects, and how we value the labor of people who work on those projects. Reading the presence and absence of people involved in the labor of digitization can tell us about what we view as important and unimportant, whether we value the labor, and what we have been willing to compromise.

The work undertaken to digitize collections occurs within societal and political contexts and underscores the reality that archives are not neutral. As such, our value systems are reflected in those projects and their outputs. In the rest of this presentation I want to consider this from two angles: the traces of people in digitized resources, and the presence of people in the discourse around digitization projects, such a articles, conference presentations, and the like. I hope that this framing is useful in considering how projects are conceptualized at their beginning, how we disseminate information about them, and how they can be interpreted in the future.

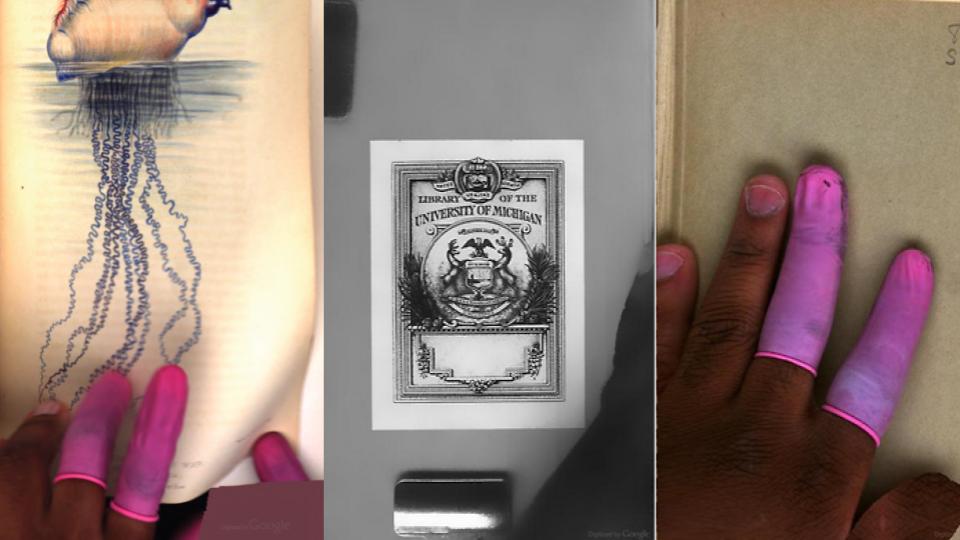

We see traces of people in digitized materials usually through the the presence of the person doing the imaging. Writer Kenneth Goldsmith describes the work of a number of artists including Benjamin Shaykin, Andrew Wilson, and Krissy Wilson as “artful accidents” in the context of Google Books. Here we can see an example of this: the presence of a scanning operator’s hand. Goldsmith seems to play at the uncanny aspect of this, but what is it that’s precisely the most discomforting about this image? Many of you will notice that hands portrayed in images from Google Books are those of people of color. Consider that images like this one are also considered an aberration, and the absence of the operator is viewed as desirable.

What happens in the cases we willingly choose to correct, or overcorrect that presence? Overcorrections like the ones in this image, which are largely applied using computer vision algorithms, What are the motivations for leaving such traces at all? What is the imperfect removal of the trace supposed to address? This sort of change suggests that perhaps the idealized surrogates one where the operator is the least present.

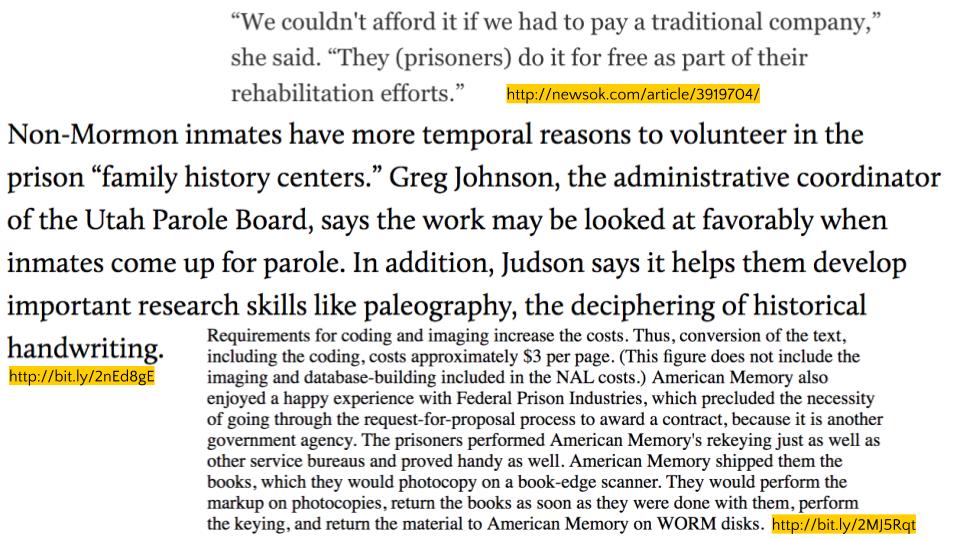

By comparison, let’s now consider how we talk about digitization when we report out on our projects regarding the labor used within them. I have found a number of excerpts from descriptions of projects that use prison labor for digitization and text encoding. When we read these excerpts we can notice two things: the recognition that the use of the labor of incarcerated people is read as a positive thing, given its cost effectiveness and the fact that it is viewed as “helping” incarcerated people - either in an abstract way, to reflect “good behavior,” or perhaps even job training. At the same time, we notice an undercurrent that without the availability of incarcerated people to digitize these materials, the prospect of digitization would be unaffordable.

As we consider the presence or absence of people and their labor involved in in digitization production, we must also consider how our projects, and not just the underlying intellectual work of the surrogates we produce, impact and document the labor of those involved. I ask you to consider your choices around project design you credit those who have contributed to your project. Cost effectiveness is a two-way street, with lasting ethical implications.