Collaboration Before Preservation: Recovering Born Digital Records in the Stephen Gendin Papers

For some, the phrase “born digital resources” may be unfamiliar, but Ricky Erway, Senior Program Officer at OCLC Research wrote a brief essay entitled Defining “Born Digital”, which provides a handy, working definition: “items created and managed in digital form.” Manuscripts and Archives, the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, and Yale University Library overall have had a notable history of working with born digital resources over the past ten years.

Past projects undertaken within the Yale University Library have included the Fedora and the Preservation of University Records project (funded by the National Historical Records and Publications and Records Commission, in collaboration with Tufts University Digital Collections and Archives), Michael Forstrom’s case study of the George Whitmore papers in the Beinecke 1, the migration of government information on CD-ROMs and DVD-ROMs 2, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation-funded project Born-Digital Collections: An Inter-Institutional Model for Stewardship (AIMS), a collaboration between Yale, University of Virginia, Stanford University, and University of Hull. In 2012, the AIMS project received an National Digital Stewardship Alliance Innovation Award.

Manuscripts and Archives shares a lab space for working with born digital records and obsolete media with the Beinecke. The lab began as a result of our collaboration with the Beinecke on the AIMS project, and now a few years after it began, we have one of the best facilities in the northeastern United States to work with old computer media formats. Our equipment includes consumer-grade computers and drives for a variety of media formats (floppy disks, compact discs and DVDS, Iomega Zip disks, etc.), as well as some specialized equipment, such as forensic write blockers, which prevent a computer or its operating system from modifying the data on a disk or device during the transfer process. We have recently begun a project to begin arrangement and description for a number of collections that contain born digital records. While MSSA staff including myself will be writing more in the future about processing these collections for this blog, I wanted to write a post about a specific example within one of the collections we are processing that emphasizes the importance of collaboration both within Yale and beyond about our efforts to preserve and provide access to born digital records.

MSSA holds the papers of Stephen Gendin (1966-2000), a lifelong HIV/AIDS activist and writer. Gendin’s activism started soon after he tested positive for HIV as a freshman at Brown University. Gendin was an early member of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), a direct action-focused group, and he founded ACT UP/Rhode Island in 1987. With Sean Strub, in the early 1990s Gendin co-founded the Community Prescription Service, a business and advocacy group for patients requiring FDA-approved drugs for treatment of HIV/AIDS. With the exception of the born digital records within the collection, Gendin’s papers have been processed. After consulting with Arrangement and Description Archivist Matthew Gorham, who originally processed this collection, and Mary Caldera, MSSA’s Head of Arrangement and Description, I agreed to assist with the processing of the born digital records within the collection.

The born digital records within Gendin’s papers, which were created approximately between 1985 and 2000, were received on a variety of removable computer media, including 3.5" and 5.25" floppy disks, a CD-ROM, and a SyQuest 44 megabyte 5.25" removable hard disk cartridge. While we have established some infrastructure and procedures for working with very common computer media formats, this would be the first time in which we had to work with SyQuest cartridges. While not necessarily uncommon when they came to market, today SyQuest cartridges are now very difficult to read because the original drives are very hard to find.

SyQuest 44 MBs. Photo by portmanteaus.

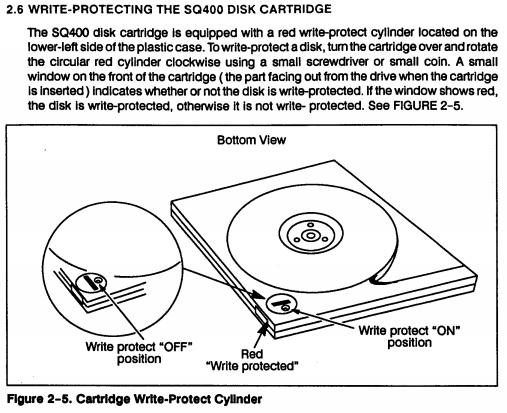

My first goal was to set forth and find a drive that could read these cartridges, and I turned to my network of colleagues who had similar expertise and equipment. Don Mennerich, a MSSA alumnus and a digital archivist in the Manuscripts and Archives Division at the New York Public Library, has a similar lab as we have within the Sterling Memorial Library, and I scheduled time to visit him. Don had a SyQuest drive that he was not able to get working, so the first order of business was to see if I could help him make it work. After spending about an hour or so there, we made no progress, but he agreed to lend me his drive on the condition that he could visit our lab at Yale to transfer data from a SyQuest cartridge in NYPL’s holdings if I was able to get it to work. I did some research on SyQuest cartridges and found documentation about how to write-protect them thanks to Al Kossow’s Bitsavers project, which is an online repository of software and documentation for old computers. Kossow, a former software engineer at Apple, is the Robert N. Miner Software Curator of the Computer History Museum.

Write-protecting the SQ400 disk cartridge. [^3]

I brought the drive to our lab the following week, and tested it with similar combinations of hardware. After remembering that Michael Forstrom, an archivist at the Beinecke, had brought over an Apple PowerBook G3 “Wallstreet” laptop for our potential use in the lab about three years ago, I realized that I could likely get the borrowed drive working with that computer, and asked Gabby Redwine, the Beinecke’s digital archivist to confirm this. The “Wallstreet” PowerBook G3 has been described by Doug Reside as “Rosetta machine” given its ability to act as “a translation aid for those wishing to transfer information from one encoding to another.” 3 In particular, the PowerBook in our lab has a SCSI port, to which we could connect the SyQuest drive, as well as a drive for Zip disks, with which we could transfer the data to a more recent machine. After a bit of trial and error, I was able to get the PowerBook to recognize the drive and to read the disk, which appeared to contain several databases.

Even though we were able to read the cartridge, my colleagues in Manuscripts and Archives and I still have a good amount of work in front of us to process the born digital records in Gendin’s papers and to integrate the description of those records into the existing finding aid. In the words of Erin O’Meara’s presentation from the OCLC Research Past Forward conference at Yale University this summer, “no one cooks the bacon alone.” In other words, one person cannot do all of this work in isolation – it requires collaboration within the department and institution, and it requires drawing on a variety of expertise, including knowledge about the collection and its creator, that of the archivists who have previously processed these and similar collections, and those of us who have expertise and knowledge about current and obsolete computer technology.

Thinking beyond this sort of collaboration, it should be clear that, as MSSA’s digital archivist, even I needed to draw on a strong professional network to be able to even begin doing this work. Our lab did not have the equipment necessary to work with these materials, so I had to connect with colleagues like Don and Gabby, and use community resources such as Bitsavers as my base of resources and knowledge for obsolete and now rare storage technology. Ben Fino-Radin, formerly the digital conservator at Rhizome, writes in his post “It Takes A Village To Save a Hard Drive” about the experience of recovering and transferring the work of artist Phil Sanders during the New Museum’s XFR STN exhibition as one that needed to leverage a grassroots network that brought together equipment, practicing artists, cultural heritage and preservation professionals, computer history experts and enthusiasts, humanities scholars, and beyond. While more and more academic research libraries such as the Yale University Library grow their capacity to work with born digital content, it is clear that we will not be successful unless we also continue to develop and leverage a strong community based on expertise, trust, and collaboration.

In that spirit, I will continue to share the information that I gain in working with these materials, both on this blog and in other channels such as the Yale ERecs blog about my work and my discoveries. In particular, I will be writing a more detailed blog post about the work I’ve undertaken with the media and records in the Stephen Gendin papers and in other collections I help to preserve and make accessible for our patrons.

References

-

Michael Forstrom, “Managing Electronic Records in Manuscript Collections: A Case Study from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.” American Archivist 72(2) (2009): 460-477. ↩︎

-

Gretchen Gano and Julie Linden, “Government Information in Legacy Formats: Scaling a Pilot Project to Enable Long-Term Access.” D-Lib Magazine 13(7/8) (2007). doi:10.1045/july2007-linden ↩︎

-

Doug Reside, “Rosetta Computers.” Digital Forensics and Born-Digital Content in Cultural Heritage Collections, Matthew G. Kirschenbaum, Gabriela Redwine, and Richard Ovenden. CLIR Publication No. 149. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources, December 2010, p. 20. Available from http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub149/. ↩︎